Originally published in City AM, Tuesday 16 August 2016

Anyone who has been to Levi Roots’ Caribbean Smokehouse will know that success on Dragons’ Den does not a restaurateur make. So it was with some trepidation that I approached Texas Joe’s, opened off the back of an appearance on Dragons’ Den (and, more recently, a number of London pop-ups) from jerky peddling Texan Joe Walters.

On-screen investment partner Peter Jones is no longer on the scene and Walters is now in partnership with local businessman Simon Lyon. They’ve chosen a canny spot, an old Chinese take away site on the route between Bermondsey Street and London Bridge.

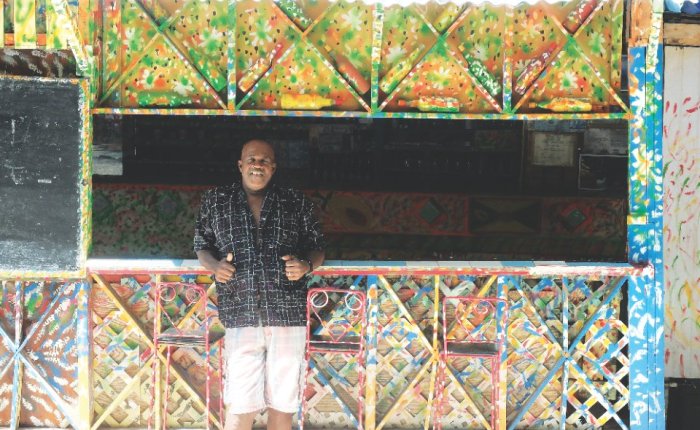

Texas Joe’s has gone all out in bringing the Lone Star state to London. The front of the shop is clad with dark clapperboard and the interior filled with hand painted signs. The newsagent next door looks in dire need of a lick of paint next to the film set facade.

The eponymous Walters is a wonderful front man. Squeezed into a dusty blue suit, stetson on his head, mouth firmly stuck in a frown, like a child’s drawing of a bloodhound. He has the look of a man who has spent hours looking into a burning pit, willing everything to turn out right. Standing arms folded outside his new restaurant, he gives the impression this might be the most serious job in the world.

The seriousness continues inside. There’s real attention to detail here. The menu is delivered in a newspaper that features articles specially written for Texas Joe’s by some of the world’s foremost BBQ experts. No fluff or hoopla, just the good honest history of meat and fire.

Outside are trestle tables and benches, while inside is divided into two handfuls of tables, some in the main room and a few more in the next-door bar. On the night I visited they were fully booked and people were regularly turned away.

Yes, it is all on the edge of OTT, in danger of falling off a cliff into a clichéd cavern of kitsch, but it holds on, never quite feeling forced. The staff play a big part, a rag-tag bunch of wonky smiles and bright eyes who seem genuinely eager to please.

At dinner we order a number of dishes to share. Starting with the sides menu we hoover through brisket topped nachos, neatly arranged on a tray like canapés at a Texan wedding.

Bacon wrapped stuffed jalapeños make a plate of padron peppers between layers of salt and pork into a must-order dish; they’d be worth a second round if they weren’t £7.

There’s more beef brisket, this time in thick dark crusted slices that break apart with the press of a fork. Chicken breast is majestic in a way that a chicken breast never is – deep and moist and moreish. The first bite of a mutton rib is equally good. Hot, crisp and musky. But as the tray cools the fat starts to flab and some went uneaten. If you order these, eat them hot.

Mac and cheese is as gooey and yellow as you could hope but I get significant food envy watching lengths of bubbling bone marrow being carried to the table next door. Next time.

Everything from the pit is served with pickles and slaw and slices of white bread to mop up the juice. If there’s a better use for a piece of cheap sliced white, let me know.

They’ve got lunch sorted too: I went back for that bone marrow and a pork taco that’s so far removed from the ubiquitous slop often served at pubs that I wonder if it is from a different beast altogether.

Drinks are dispensed from the honky-tonk bar next door. There’s beer – from Texas, of course, as well as some South London breweries – and a selection of bourbon and tequila. The bar works in its own right too: a beat-up juke box is full of country classics and it has a converted-garage feel that will make a wait for a table fairly painless, even when the weather turns.

The food at Texas Joe’s doesn’t push the envelope in the way somewhere like Pitt Cue does. The real selling point here is tradition and respect for the craft. This is Texas BBQ with ‘Texas’ underlined, and it deserves to be taken seriously.